From Warrior to Unifier: How King Kamehameha Shaped Hawaii’s Future

Reading time: 7 minutes

October 15th, 2025

This year, we honor the legacy of Hawaii’s founding monarch: King Kamehameha. With Apple TV+’s Chief of War offering a dramatic retelling of Hawaiian history, now is a perfect moment to revisit the story of the alii who united these islands. Through military strategy, governance reforms, and diplomacy, Kamehameha laid the groundwork for a unified kingdom and continues to shape modern Hawaii.

Born around 1758 in the Kohala district of Hawaii Island, Kamehameha (originally named Paiea, meaning “hard-shelled crab”) seemed to emerge from prophecy. A brilliant light in the night sky, perhaps Halley’s Comet, which appeared in 1758, shone overhead near the time of his birth. The bright star was seen by priests and kāhuna, who foretold that a great leader was about to enter the world, one destined to rise above all rivals and unite the pae aina (archipelago) under a single rule.

Kamehameha was the son of Keōua, a high chief of the Kohala and Kona districts on Hawaii Island, and Keku‘iapoiwa II, a daughter of the former Kohala chief Ha‘ae. Despite his noble bloodline (or perhaps because of it), Kamehameha’s birth sparked fear in ‘Alapa‘i, the ruling chief of Hawaii Island, who ordered the child’s death. However, the newborn was secretly taken and hidden away, raised in safety in the remote valleys of Kohala; it was during this period of isolation that he came to be known as Kamehameha, often translated as “The Lonely One” or “The One Set Apart.”

Kamehameha returned from exile around the age of five and was brought to the royal court of his uncle, Kalani‘ōpu‘u, who had by then become the ruling chief of Hawaii Island. There, he received a rigorous education in navigation, oral history, warfare, and religious ceremony. He also participated in elite athletic competitions reserved for the alii, such as oo ihe (spear throwing), ulu maika (stone disk rolling), and hakoko (wrestling). Kamehameha was being prepared not just as a warrior, but as a leader.

As a teenager, Kamehameha’s physical prowess became legendary. According to tradition, he overturned the Naha Stone, a multi-ton volcanic boulder said to move only for the one destined to unify the islands. By the late 1770s, Kamehameha continued to earn a reputation as a figure of strength as well as political promise. He was among the alii who interacted with Captain James Cook’s expedition when the HMS Resolution and Discovery anchored off Hawaii Island in 1779.

When Kalani‘ōpu‘u died a few years later, his son Kīwala‘ō inherited control of Hawaii Island while Kamehameha was given guardianship of the war god Kūka‘ilimoku. The right to serve as caretaker for this symbolic figure of conquest and authority was typically reserved for the ruling chief; to bestow that honor on a person other than one’s heir was both unusual and politically provocative. It implied not only trust in Kamehameha’s spiritual dedication but also represented a divine endorsement of his future leadership—and planted the seeds of a rivalry between the two cousins. One that would culminate in the Battle of Mokuohai near Keei in Kona, where Kamehameha challenged his cousin’s authority. Kīwala‘ō was killed in the fighting and Kamehameha claimed control over much of western Hawaii Island.

Over the next two decades, Kamehameha expanded his power through warfare and diplomacy. After consolidating his rule over all of Hawaii Island by 1791, following the death of rival chief Keōua Kuahu‘ula, he turned his sights to the neighboring islands. Kamehameha cultivated relationships with foreign traders to secure weapons, such as muskets and cannons, which would give him a significant advantage on the battlefield. He strengthened his naval force by acquiring Western vessels, including the schooners Fair American and the Lelia Byrd, the latter of which would eventually serve as the 175-ton flagship of his navy.

Two foreign sailors, John Young and Isaac Davis, who had become trusted advisors after arriving in Hawaii in the early 1790s, played a pivotal role in training Kamehameha’s warriors. Their guidance, combined with Kamehameha’s own leadership and tactics, helped transform his forces into one of the most formidable in the Pacific.

In 1795, Kamehameha launched a major military offensive. His forces quickly secured Maui and Molokai. The campaign culminated in the fierce Battle of Nuuanu, where Kamehameha’s men drove the defenders of Oahu, led by Chief Kalanikūpule, through Nuuanu Valley, forcing many to fall or be pushed off the 1,000-foot cliffs of Nuuanu Pali. It would take another decade before Kauai and Niihau joined the kingdom (through peaceful negotiation rather than bloodshed) when King Kauamuali‘i agreed to remain chief under Kamehameha’s authority in 1810.

As leader of a unified Hawaii, Kamehameha governed with a blend of traditional authority and innovation. He maintained the kapu system, a strict set of sacred laws, and upheld religious customs. But he also made strategic alliances with foreign traders and advisors to expand Hawaii’s role in Pacific commerce.

Kamehameha asserted control over the islands’ lucrative sandalwood trade. Recognizing its value in the Chinese market for medicine and incense, Kamehameha created a royal monopoly: he alone set export terms, negotiated with foreign merchants, and took a large share of profits. He even placed kapu protections on younger sandalwood trees to preserve them. This oversight helped finance the purchase of weapons and luxury goods and started to shift Hawaii away from subsistence and towards a cash economy.

Kamehameha also demonstrated a deep sense of justice and protection for his people. One of his most enduring legacies was Kānāwai Māmalahoe, the Law of the Splintered Paddle, which protected noncombatants—women, children, the elderly, and the defenseless—from abuse, even in times of war. The law grew out of an incident years earlier, during a military expedition in Puna on Hawai‘i Island, when Kamehameha pursued fishermen fleeing along the shoreline. In the chase, Kamehameha’s foot became caught in a reef. One of the fishermen struck him in the head with a paddle that splintered.

“Had it not been that one of the men was hampered with [a] child and their ignorance that this was Kamehameha with whom they were struggling, Kamehameha would have been killed that day,” wrote 19th-century Hawaiian historian Samuel Mānaiakalani Kamakau in Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii. Years later, when that same fisherman was brought before Kamehameha for trial, the chief ruled that he had acted out of fear and defense of his land and family.

“While the fisherman trembled … and lay at the conqueror’s feet in expectation of some dire punishment, Kamehameha was generous and just,” wrote scholar Herbert Henry Gowen in The Napoleon of the Pacific. “Kings are not always so willing to pass retrospective judgment upon their own escapades.” Kamehameha responded not with vengeance but compassion. He issued a royal decree: “Let every elderly person, woman and child lie by the roadside in safety.”

As part of his efforts to consolidate power and secure the future of his kingdom, Kamehameha cultivated strong diplomatic ties with Great Britain, the dominant naval power of the era. He maintained friendly relations with British officials, most notably George Vancouver, who gifted livestock, including longhorn cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as strategic counsel. Kamehameha also moved his royal court from Hawaii Island to Honolulu on O‘ahu, which had emerged as a vital hub for international trade.

To ensure a smooth transition of power, he named his son Liholiho as heir. After Kamehameha’s passing, his favorite wife Ka‘ahumanu declared that Kamehameha had entrusted her with shared authority. Backed by her chiefly position and political support, Ka‘ahumanu assumed the new role of Kuhina Nui, or co-regent, further shaping the governance of the young kingdom.

Kamehameha the Great died in 1819, leaving behind a unified kingdom, unprecedented in the archipelago’s history. Under his successors, the Kingdom of Hawaii would go on to earn formal recognition from major world powers, including Britain, France, and the United States. Revered as a thoughtful strategist, skilled leader, and a ruler with a strong sense of justice, Kamehameha remains one of Hawaii’s most enduring symbols of strength and unity. His impact echoes throughout stories passed down through generations, as well as in the land, laws, and spirit of Hawaii itself.

This story is presented in partnership with Nā ‘Ōiwi Aloha, an employee resource group of Native Hawaiians and allies at Bank of Hawaii committed to advocacy, education, and community engagement.

Kamehameha’s legacy continues to inspire generations. To learn how Bank of Hawaii is continuing to honor and uplift our local communities, visit https://www.boh.com/community.

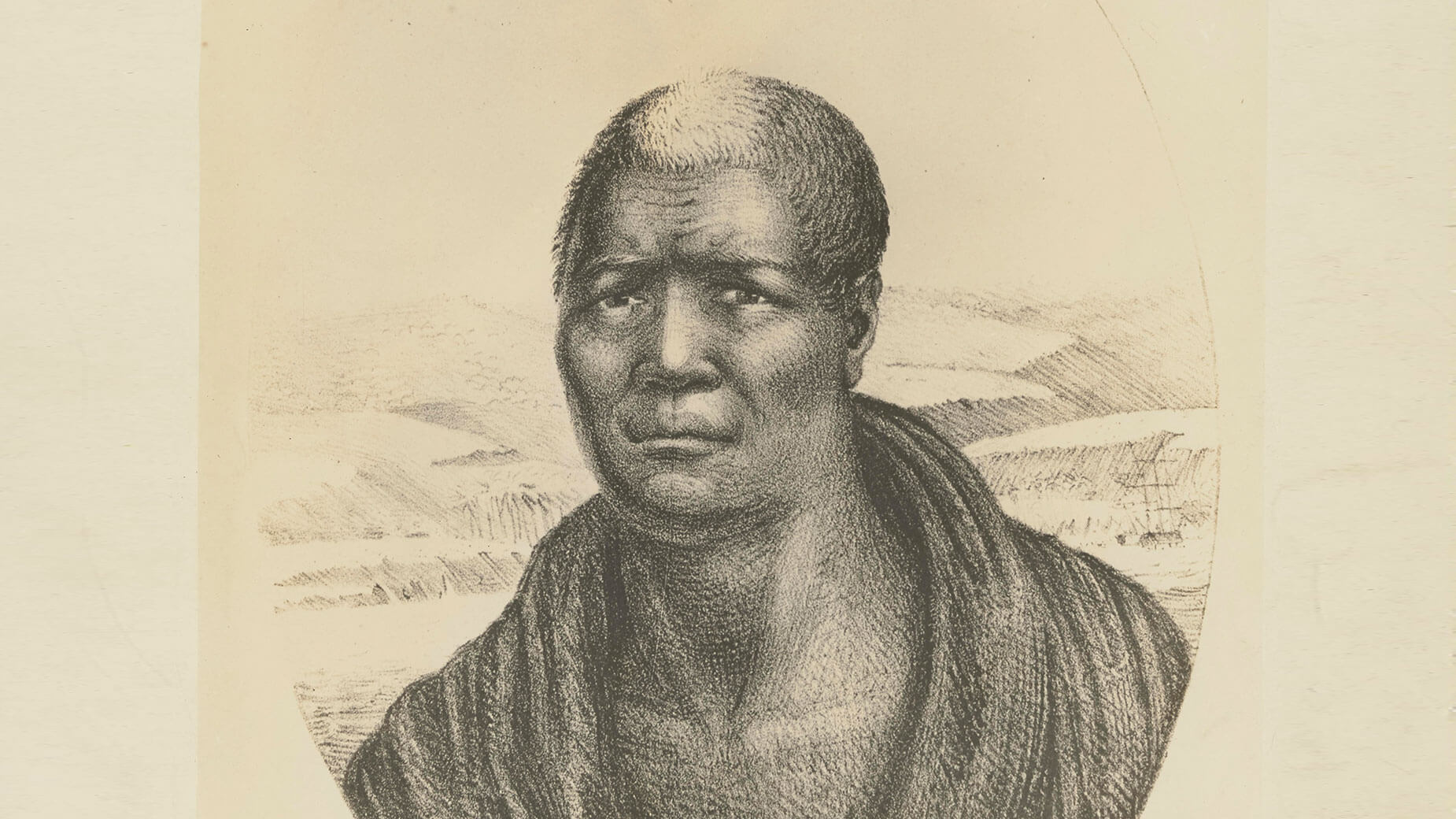

Photo credit: Hawaii State Archives, Photograph Collection, PP-97-5-004

You're about to exit BOH.com

Links to other sites are provided as a service to you by Bank of Hawaii. These other sites are neither owned nor maintained by Bank of Hawaii. Bank of Hawaii shall not be responsible for the content and/or accuracy of any information contained in these other sites or for the personal or credit card information you provide to these sites.